From drones to body cameras, the continued growth of new technology for Fire and Rescue Services (FRSs) promises a complete overhaul of frontline operations. One particular area of development which can be particularly transformational is that of purpose-built mobility platforms – such as Motorola Solutions’ Guardian Mobile (formerly MODAS) – which centralise and mobilise key incident command tasks into one intuitive, source-agnostic user interface for use on a Mobile Data Terminal (MDT), phone or laptop. With this context, firefighters can make more informed choices throughout the incident, while command support and mobilisers can coordinate remotely.

To understand the true impact that mobility apps can have on every stage of frontline operations, we spoke to veteran incident commander Randy McComb about his experience using these applications on the fireground itself. In his 29 years with Northern Ireland FRS, Randy has held a broad spectrum of roles – including station and district management, prevention and protection, operational response and resilience – before eventually leading the service’s learning and development centre. All of this experience makes him well-versed in the challenges that these teams face, and how technology is best positioned to help.

Using better data to make better decisions from the very start

Randy emphasises that in order to make the right decisions on the fireground, teams need access to the most accurate, up-to-date information possible – as soon as they leave the station. When he first started, the process for getting that context was very rudimentary: “We had A4 cards in the fire engine which had risk information pertaining to specific locations around our station ground, and we had to read those en route to the incident while also using paper maps to navigate. If I was attending a call somewhere else, we simply wouldn’t have that information available because you could only carry so much paper with you on the back of an appliance.”

Randy explains that now, with mobility applications presented on the MDT installed in the appliance itself, everything has changed. “When a call comes in, the first thing the MDT tells you is where you’re going and how you’ll get there. Then, you can view the critical information pertaining to the location – is there a padlock on the gate? Do you need a ladder to get over the gate? Is there a hydrant nearby? That information allows the initial incident commander to start thinking about the actions they need to take on scene.”

The responding crews can access turn-by-turn navigation straight to an incident, using location information from a FRS’s Computer-Aided Dispatch (CAD) system.

He notes that, due to cloud architecture, this increased situational awareness isn’t limited to crews in the field. Station officers can stay informed via tablets or TVs in break rooms, enabling different teams to gain a high-level overview of an incident without tying up radio channels.

A final key differentiation between pen-and-paper methods and these mobility platforms is the consistency of information between members of the same Service: “Now, every appliance in an FRS has the same data available to them. That’s important when you’re dealing with large geographical areas – for example, Northern Ireland has 67 fire stations – because you can be aware of the risks at a location regardless of which station you’re actually based at.”

Establishing a common operating picture for closer cross-agency collaboration

Mobility applications don’t just help crews during the initial stages of an incident. “It’s all about gathering and disseminating information to the entire command team, as and when they need it, so they can continuously develop and review the most effective plan as the incident evolves,” says Randy. These apps can enable commanders to easily transfer roles and a log of previous actions, enabling smoother handoffs in the field.

Randy continues, “After the initial command team – L1 crew managers and watch managers – complete the first risk assessment, the L2C station managers will start to examine the wider impacts of the incident if needed. FRSs have a legal responsibility to mitigate any environmental harm, so they’ll need information about the surrounding area and potential risks there.” Purpose-built apps can provide that context, such as vulnerable populations, potential water runoff routes and even data about hazardous chemicals, on one map for easy consultation. As an incident evolves, FRS plans need to adapt, too: teams can update sectors and evacuation plans with just a few taps of a touchscreen. This kind of dynamic planning is especially necessary during high-rise building fire: “Commanders can keep track of how many people are still in the tower block and where they are, to better triage and prioritise their response. It’s such an asset to have that kind of visibility.”

Incident commanders can view a detailed map of all victims in a high-rise building, in order to rapidly identify and prioritise vulnerable individuals.

Finally, at the senior level, members of the tactical/strategic coordination group need to work with other agencies – including police, ambulance and the local councils – to establish a shared understanding of the incident. “Fires don’t stop with a FRS. The police may need to deal with road closures, manage outer cordons or deal with potential unrest, the ambulance service prioritises the treatment of any casualties, and so on.” By synchronising information between all of these agencies, mobility applications ensure that disparate teams are coordinating their responses and covering all bases. Commanders can build organisation charts on an MDT or tablet, so all parties involved are aware of reporting structures and who to approach for assistance. And once an incident has been resolved, senior stakeholders can use the app to build debriefing documents which capture all actions taken throughout the response; this is crucial for both internal training and external investigations, where necessary.

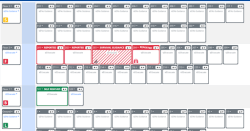

Senior stakeholders can see a full view of the incident, including resources and cordons.

As Randy sees it, seamlessly integrating all available data into a mobile platform is fundamentally transforming the way fire and rescue services make life-saving decisions. Whether it’s pre-incident planning, on-scene coordination, or post-incident review, these applications are equipping FRSs with the clarity and connectivity needed to operate effectively in the most critical of circumstances.

Learn more about Guardian Mobile at motorolasolutions.com/guardian